Jeff Olsson | The Thoughts of Vegetables

(Scroll down for Swedish)

We are pleased to announce Jeff Olsson’s second solo exhibition in the gallery; The Thoughts of Vegetables. Ann-Charlotte Glasberg Blomqvist writes about the exhibition:

I look at nature

Nature looks at me

Aase Berg, Liknöjd fauna (Indifferent Fauna), 2011

When encountering the art of Jeff Olsson, I find myself alluding to notions that actually describe it in a far from satisfactory manner.

Nature. Landscape. Man. Animal.

They are all embedded in the motifs of the drawings, and yet, not. If the notions are meant to designate and distinguish various phenomena from each other, and thereby enable an understanding of the world, then the manner in which they behave in the drawings achieves the opposite. The components of the images merge and are forced off course: the character traits of the landscape find their way into the bodies of the human figures, who in turn take on an animal-like appearance. What is what?

Changes have taken place in the art of Jeff Olsson in the past year or so. In the exhibition The Thoughts of Vegetables, the pencil drawing has now transitioned into a form of painting where graphite powder and emulsion are applied with a brush, which lessens the degree of control regarding the execution of the image and offers the haphazard a more decisive role. His earlier drawings often featured landscape scenes with groups of people involved in ambiguous and often contradictory activities, resembling surrealist encyclopedia posters. These have now yielded for a more intense focus on the individual. Less tableaus and more portraits, to use visual culture terms in describing the transition. Instead of being opened towards scenographic forest glades, nature and the forest landscapes take on the semblance of raw material. Everything is dark and diffuse. Horizon lines in the drawings could have facilitated overview and orientation, but these seldom appear, and thus the viewer is thrust into the dark folds of matter.

I see two dominating threads in Jeff Olsson’s works that both merge and intersect. The one possesses a surrealist quality and describes items, creatures and occurrences that are in logical conflict. They are positioned and intertwined in an unexpected, boundary-transgressing and dream-like manner, giving them a powerful charge. The boundary between illusion and reality depiction is eradicated. The other has a strain of civilization critique and is associated to that which normally is referred to as post-humanism; discussions dealing with how we can reassess and manage the world without placing mankind at its absolute center. Banishing man from this privileged perch arouses fear, but also hope. In The Scholar, a conflict is manifested: mankind – or rather the human being – is undergoing changes in relation to origin and the animal, but she appears nevertheless as a headstrong, modern homo sapiens in her desire to study and penetrate the material itself. She sticks her hand in the hole, simply because it’s there.

In the drawings, it is as though the human figures are incapable of offering opposition to the surrounding landscape. It grows out from, or into, their bodies. It alternates between covering and enveloping on the one hand, and penetrating on the other. It is a violent relationship.

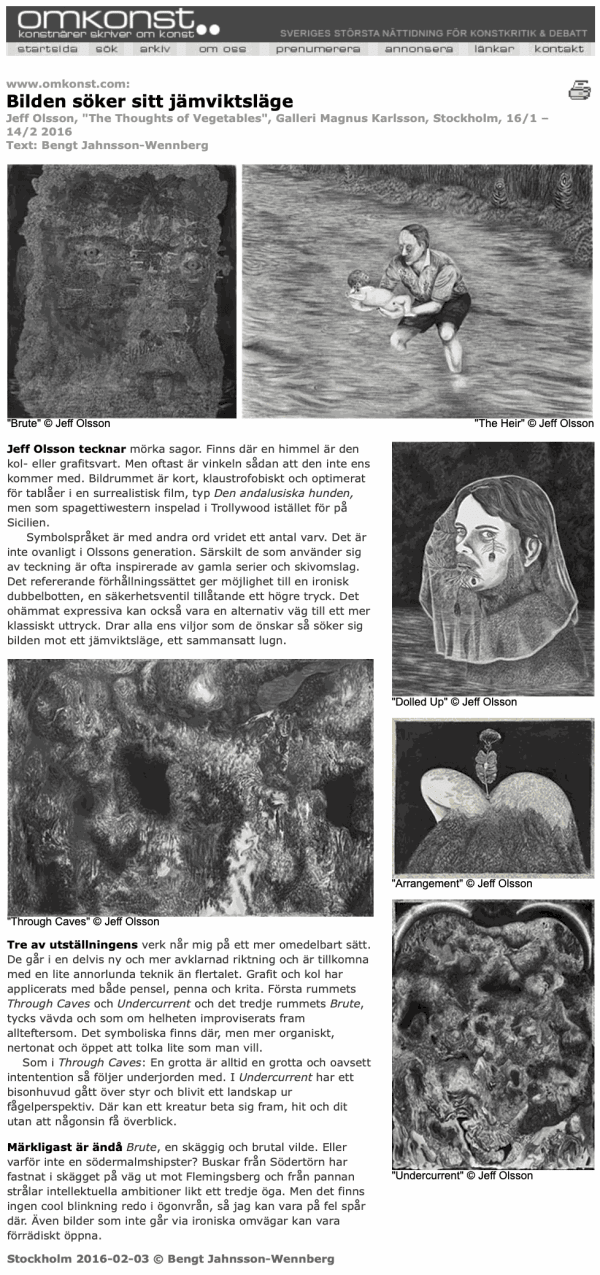

In Brute, a face emerges from a profusion of patterned surfaces. The eyes, nose and mouth are placed out of proportion and give the face an almost groggy expression. One can discern facial hair, skin disease and decay in the surfaces, but it is primarily as lichens and moss that I consider them fathomable. As though the face emerged directly from a mountain and pulled all the vegetation along with it.

Similar images of matter and material suddenly coming to life and revealing another form of reality can be found in both older and newer myths, fairytales and horror stories. Western man’s point of departure has long been to view nature as being there for the taking, something to be vanquished by mankind herself. The conviction of man’s privilege over nature, as though we ourselves are not a part of it, has run unabated from the time of the Biblical creation myth to the climate changes of our era. But all the while, notions of a spiritual world has stubbornly lived on.

The notion of nature, that has been borrowed from the Latin natura, has most frequently been defined as all that humankind cannot create. Today, that perspective has partially shifted; much is said nowadays with regard to what extent humanity’s direct and indirect influence on our living environment has resulted in visible consequences even in areas beyond her physical presence. There is no such thing as pristine nature any longer, not even on at the South Pole. A new geological era, anthropocene, has been proposed to designate our modern time. Is nature, in its previous meaning, on the verge of disappearing?

Kerstin Ekman points out in her essay compilation, The Gentlemen in the Forest, that the Swedish words for forest and beard stem from the same Nordic word, skogher, that indicates something that sticks out or protrudes. The word has a germanic root, and first came about at a time when forests covered most of Northern Europe. Ekman sadly notes that the meaning of the term has lost its validity today. The forest is no longer something that sticks out into the agricultural landscape but is to a large extent part of it, subservient to economic rationality and product estimates.

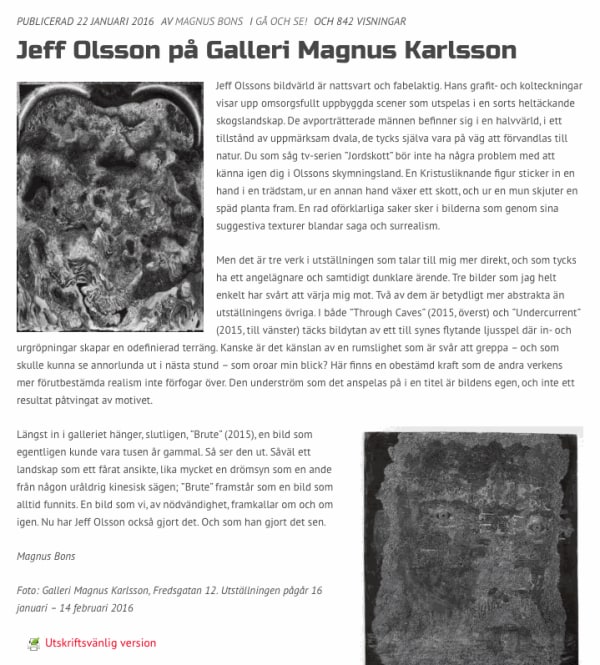

If the forest in The Thoughts of Vegetables is thick and mystical – referring rather to the remnants of primordial forests than to deforestation – then the beard has a more ambivalent purpose. The meticulously trimmed hipster mustache in Dolled Up is set in contrast to the thick fur-like hair covering on the man's neck and shoulders. Where the one refers to the urban trend markers of our time, the other points to hairiness as something outside of culture.

The tone in Jeff Olsson’s works has darkened. Not only due to the fact that the graphite's blackness has deepened in a physical sense, but also because the figures in the motif seem to have abandoned the complacent existence in the earlier drawings, to make their way towards considerably more brutal domains. But the playfulness lingers on nevertheless. Both in the title of the exhibition and the face in Brute, I sense a darker nod towards Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s humorous portraits of the 1500s, composed of vegetables, fruit and berries. Potent gentlemen with rosy peach complexions gazing out over the world with their cherry eyes. What might they be thinking?

Ann-Charlotte Glasberg Blomqvist

Art critic and junior lecturer at Valand Academy, University of Gothenburg

Parallel to this exhibition Jeff Olsson is also part of a two-person exhibition along with Joakim Ojanen at Passagen, Linköping Konsthall, Sweden 23.1–6.3 2016.

Jeff Olsson was born 1981 in Kristinehamn, Sweden. He lives and works in Gothenburg, Sweden. Education: Gerlesborgskolan (2001–2003) and Valand Konsthögskola (2003–2008). Selected solo exhibitions: Market Art Fair (2014), Krets, Malmö (2014), Jack Hanley, New York (2013), Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stockholm (2010, 2011), Galleri Thomassen, Göteborg (2009) and Galleri Big Love, Göteborg (2005). Selected group exhibitions: Göteborgs konstmuseum, Göteborg (2015), Strandverket, Marstrand (2015) Chart Art Fair, Köpenhamn (2014) Konsthallen–Bohusläns museum, Uddevalla (2014), Frieze Art Fair, Jack Hanley Gallery (2013), The Armory Show, New York (2011, 2012), Garemijn Hall, Bruges, Belgien (2012), Needles and Pens, San Francisco (2010), Liljevalchs Vårsalong, Stockholm (2009), Göteborgs Konsthall, Göteborg (2008) and Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm (2008)

Vi har glädjen att presentera Jeff Olssons andra större utställning på galleriet; The Thoughts of Vegetables. Ann-Charlotte Glasberg Blomqvist skriver om utställningen:

Jag tittar på naturen

Naturen tittar på mig

Aase Berg, Liknöjd fauna (2011)

Inför Jeff Olssons arbete finner jag mig hänvisad till begrepp som egentligen beskriver det på ett ganska dåligt sätt. Natur. Landskap. Människa. Djur.

De finns inbäddade i teckningarnas motiv och ändå inte. Om begreppens uppgift är att benämna och särskilja olika fenomen från varandra och därigenom möjliggöra en förståelse av världen, beter de sig i teckningarna tvärt om. Bildernas komponenter flyter ihop och tvingas ur kurs: landskapets former och arter letar sig in i de mänskliga gestalternas kroppar, vilka i sin tur antar djuriska skepnader.

Vad är vad?

Det har skett förändringar i Jeff Olssons arbete det senaste dryga året. I utställningen The thoughts of vegetables går tecknandet med blyerts över mot måleri där grafitpulver och emulsion anläggs med pensel, vilket minskar kontrollen över bildernas framväxt och öppnar upp för ett större mått av slump. De tidigare teckningarna innehöll ofta landskapsscener med grupper av människor som var inbegripna i diffusa och ofta motsägelsefulla aktiviteter, likt surrealistiska encyklopediplanscher. Nu har de lämnat plats för ett större fokus på individer. Det är mindre tablå och mer porträtt, för att beskriva förändringen i bildkulturella termer.

Istället för att öppnas upp i scenografiska gläntor framstår nu naturen och skogslandskapet som rå materia. Det är dunkelt och diffust. Horisontlinjer i teckningarna hade erbjudit överblick och orientering, men de förekommer sällan och betraktaren blir därmed nerföst i materiens mörka veck.

I Jeff Olssons arbete ser jag framför allt två spår som möts och korsar varandra. Det ena har surrealistiska drag och gestaltar ting, varelser och händelser som befinner sig i logisk konflikt. De placeras och sätts samman på sätt som är oväntade, gränsöverskridande och drömska, vilket ger dem en stark laddning. Gränsen mellan illusion och verklighetsbeskrivning suddas ut.

Det andra är civilisationskritiskt och kopplat till det som brukar kallas för posthumanism; diskussioner om hur vi kan tänka om och hantera världen utan att placera människan i dess absoluta mitt. En förvisning av människan från denna privilegierade plats väcker rädsla, men också förhoppningar. I The Scholar gestaltas en konflikt: människan – eller snarare den mänskliga varelsen – är stadd i förändring mot det ursprungliga och djuriska, men hon framstår ändå som en obändigt modern homo sapiens i sitt begär efter att undersöka och genomtränga själva materien. Hon stoppar in handen, därför att där finns ett hål.

I teckningarna är det som om de mänskliga gestalterna inte kan göra motstånd mot det omgivande landskapet. Det växer fram ur, eller in i, deras kroppar. Ömsom täcker det in och omsluter, ömsom penetrerar det. Det är en våldsam relation.

I Brute framträder ett ansikte ur ett myller av mönstrade ytor. Ögon, näsa och mun är placerade ur proportion och ger ansiktet ett nästan vimmelkantigt uttryck. Det går att spåra både skäggväxt, hudsjukdom och förruttnelse i ytorna, men det är framför allt som lavar och mossor jag tänker att de blir begripliga. Som om ansiktet sprang fram direkt ur ett berg och drog med sig vegetationen.

Liknande bilder av hur liv plötsligt ingjuts i materia och avtäcker en annan verklighet finns i både äldre och nyare myter, sagor och skräckberättelser. Utgångspunkten för den västerländska människan har varit att naturen finns där för att bemästras, av henne själv. Tron på människans privilegium över naturen, som om vi inte var en del av den själva, löper från den bibliska skapelsemyten till vår tids klimatförändringar. Men i dess skuggsida har föreställningar om en besjälad värld envist levt kvar.

Oftast har begreppet natur, som svenskan lånat in från latinets natura, definierats som allt det som människan inte kan skapa. Idag är perspektivet delvis vänt; det talas om hur människans direkta och indirekta påverkan på livsmiljön har fått synbara konsekvenser också på platser långt bortanför hennes fysiska närvaro. Det finns inget sådant som orörd natur längre, inte ens vid Sydpolen. En ny geologisk epok, antropocen, har föreslagits beteckna vår moderna tid. Håller naturen i sin tidigare betydelse på att försvinna?

Kerstin Ekman påpekar i essäboken Herrarna i skogen att orden skog och skägg härstammar från samma nordiska ord, skogher, vilket betecknar det som sticker fram eller skjuter ut. Ordet har germansk rot och tillkommer under en tid då skogen täcker stora delar av norra Europa. Ekman konstaterar sorgset att betydelsen har förlorat sin giltighet idag. Skogen är inte längre något som skjuter ut i odlingslandskapet utan är i allra högsta grad en del av det, underkastad ekonomisk rationalitet och produktionskalkyler.

Om skogen i The thoughts of vegetables är tät och mystisk – den hänvisar snarare till de spillror av urskog som fortfarande existerar än till kalhyggen – så har skägget en mer ambivalent funktion. Den noggrant groomade hipstermustaschen i Dolled up kontrasteras av den täta päls som täcker in mannens axlar och hals. Där den ena hänvisar till vår tids urbana trendmarkörer pekar den andra på behåring som någonting utanför kulturen.

Tonen i Jeff Olssons arbete har mörknat. Inte bara för att grafitens svärta har djupnat rent materiellt, utan för att motivens gestalter tycks ha förflyttat sig bort från de tidigare teckningarnas förnöjda tillvaro mot mer brutala domäner. Ändå dröjer sig lekfullheten kvar. I utställningens titel och ansiktet i Brute anar jag en mörkare blinkning till Giuseppe Arcimboldos humoristiska 1500-talsporträtt komponerade av grönsaker, frukt och bär. Potenta herrar med rosiga persikokinder som blickar ut över världen med sina körsbärsögon. Man undrar vad de tänker.

Ann-Charlotte Glasberg Blomqvist

Konstskribent och adjunkt på Akademin Valand vid Göteborgs universitet

Förutom utställningen på Galleri Magnus Karlsson så är Jeff Olsson även aktuell med en större utställning på Passagen, Linköpings Konsthall, tillsammans med Joakim Ojanen (utställningen pågår 23/1–6/3).

Jeff Olsson är född 1981 i Kristinehamn. Han bor och arbetar i Göteborg och är utbildad på Gerlesborgskolan (2001-2003) och Valand Konsthögskola (2003-2008). Separatutställningar i urval: Market Art Fair (2014), Krets, Malmö (2014), Jack Hanley, New York (2013), Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stockholm (2010, 2011), Galleri Thomassen, Göteborg (2009) och Galleri Big Love, Göteborg (2005). Grupputställningar i urval: Göteborgs konstmuseum, Göteborg (2015), Strandverket, Marstrand (2015) Chart Art Fair, Köpenhamn (2014) Konsthallen–Bohusläns museum, Uddevalla (2014), Frieze Art Fair, Jack Hanley Gallery (2013), The Armory Show, New York (2011, 2012), Garemijn Hall, Bruges, Belgien (2012), Needles and Pens, San Francisco (2010), Liljevalchs Vårsalong, Stockholm (2009), Göteborgs Konsthall, Göteborg (2008), Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm (2008) och Art Copenhagen (2007).

Läs recension på:

konsten.net

DN.se

www.svd.se

kulturdelen.blogspot.se

http://www.omkonst.com/16-olsson-jeff.shtml#