Mamma Andersson | Dog Days

Galleri Magnus Karlsson is pleased to present Mamma Andersson’s sixth solo exhibition in the gallery; Dog Days. The exhibition presents a new series of paintings which has recently been shown at Museum Haus Esters, Kunstmuseen Krefeld, Germany.

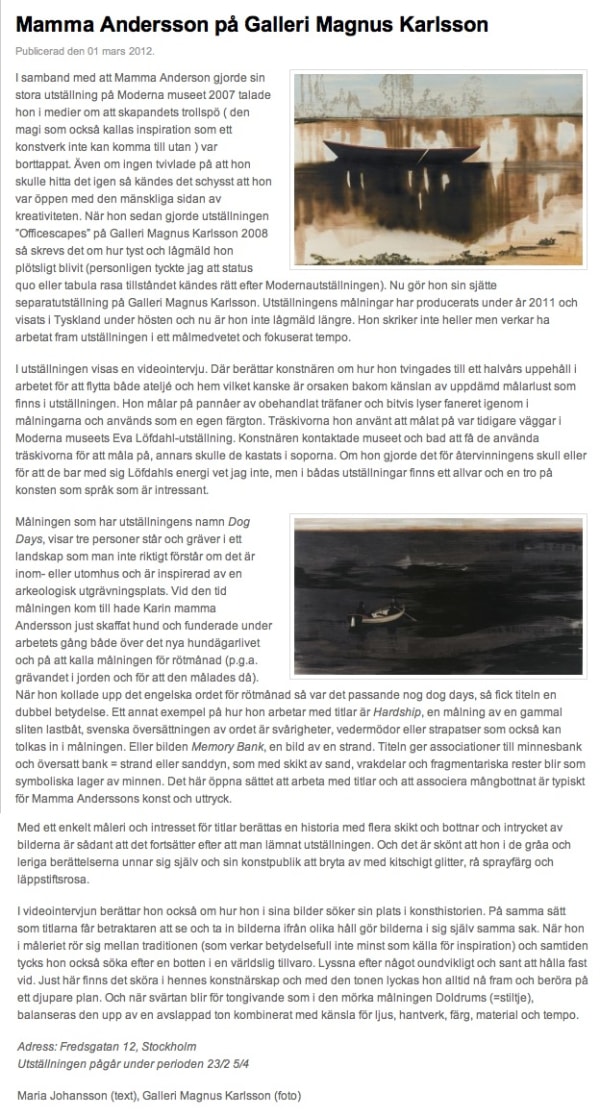

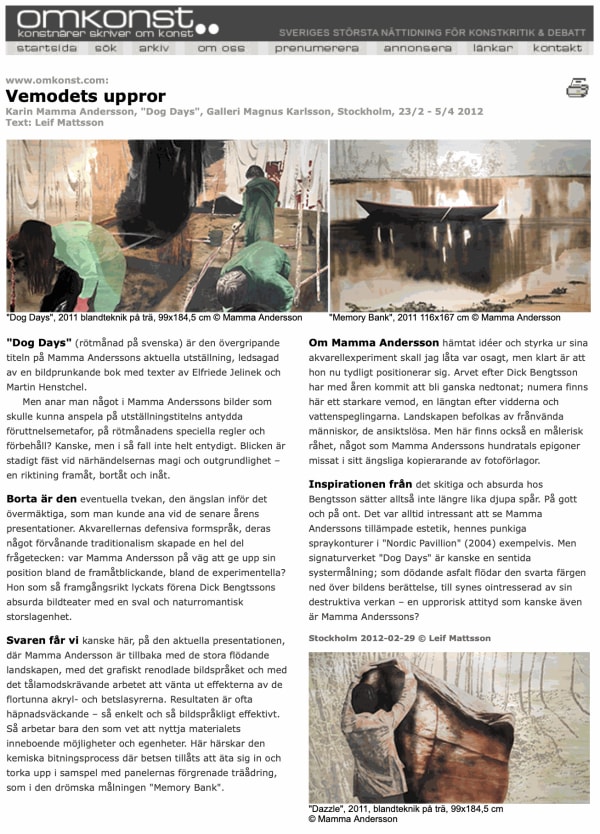

It is one of those unbearably hot days that leaves you panting for breath; not a breeze to alleviate the searing heat. But work has to go on, and it is a painstaking job. Digging up the parched soil section by section, centimetre by centimetre to find clues – that is what has brought about this torture. Three people dressed in sterile green coats have divided up the area with tape so as to keep track of it all – archaeologists of a dreadful deed that cannot have been that long ago. The toil involved is written in their every gesture. As they lean forward, we sense the burden of the work in their arching backs, their hanging smocks, their dangling hair. The only person who is standing upright is wiping the sweat from her brow. It was this figure above all that exerted a magic draw on the artist as she chanced upon the photo in a newspaper and used it as the model for her painting: an almost archetypical figure, comparable with the great heroes of antique sculpture. This gesture of wiping away the sweat is the epitome of grinding labour. And because she also keeps her eyes averted from her surroundings, she conveys a moment of growing awareness and forms as such the bridge to the viewer, who attempts to reflect on the significance of the occurrence that is depicted. Round about are isolated staves marking the location of various finds – and revealing perhaps something of the story that preceded them. The whole area is screened off from the surroundings by white sheets, presumably so as to shield innocent eyes from the horror that may ultimately come to light.

But while the protagonists are still busy with their work, the viewer has already come face to face with something else. Unnoticed by the people occupying the picture, a formless blackness is spreading out quite unexpectedly in their midst. Pitch black, dry and matt at the centre before fraying out into fluid edges, the formation pours down across the scene from above, and we witness how its effluvium unites with one of the dark areas that have been dug up.

We know such black, imponderable sections from Edvard Munch’s paintings, where they constitute emanations of psychological states – of melancholy, jealousy or mortal fear – but in his case they are always bound to the people he depicted. In Dog Days, however, the black form goes its own way, quite divorced from the actors’ psyches: a nameless calamity that will gradually take possession of the whole scene.

Almost five hundred years earlier, Albrecht Dürer painted a small watercolour that originated in a nightmare, as the artist eloquently describes in a subscript written on the selfsame sheet of paper. Das Traumgesicht [The Dream] from 1525 shows a number of enormous, seemingly apocalyptical columns of water that burst up over a wide-ranging landscape and threaten to inundate the entire country. Even if Mamma Andersson’s work is not about a nightmare, the black area in Dog Days is clearly related to the blue area in Das Traumgesicht. In both cases we are witnessing an occurrence that descends on the protagonists or the artist without any prior warning, as something fateful that brooks no escape. But unlike Dürer, in Andersson’s case the monstrosity eludes all concrete description. The title alone makes a certain allusion to old superstitions, to the “dog days” – the time between the end of July and the end of August as a period of misfortune accompanied by crop failures, sickness and poisoned water: something that the world today has come to experience as a permanent state. Seen as such, Dog Days does not really convey a crime investigation; the painting points rather to the archaic power of the inexplicable which, with one fell blow, can turn the normal course of things on its head.

Excerpt from a text by Martin Hentschel, Director, Kunstmuseen Krefeld.

The full text is included in the new book Dog Days, published by Kerber Verlag. The book, 108 pages, and also includes a new text written by Nobel prize winner in literature Elfriede Jelinek.